Study: Doctors' Word Choice Affects End-of-Life Decisions

People were 20 percent more likely to choose DNR if it was phrased as "allowing natural death;" 25 percent if they were told it's what most other people choose.

PROBLEM: "I think that's the most urgent issue facing America today, is people getting medical interventions that, if they were more informed, they would not want," said Dr. Angelo Volandes in the May issue of The Atlantic. "It happens all the time." Doctors struggle with how to explain end-of-life care to patients and to the people who are asked to make these decisions for them, and next-of-kin sturggle with the fear of not doing what's best for their loved one. Especially if what's best may be to do nothing.

- The New Less-Social Psychology of China's Generation Without Siblings

- Erections Tell Us About Our Hearts

- Hearing Music as Beautiful is a Learned Trait

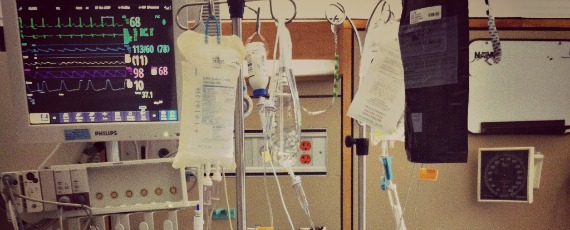

METHODOLOGY: Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh designed a web simulation that was distributed to volunteers across eight U.S. cities. The 256 participants were asked to imagine that their parent or spouse had been admitted to the ICU (in some cases, using a photo of said loved one to make it seem more "real") -- and that they had a 40 percent chance of dying. They then met, over webcam, with a physician (actually an actor) about their options for what should happen if the person's heart were to stop. In that scenario, the doctor told them, CPR had only a ten percent chance of working. The researchers manipulated the doctor's words and demeanor in all different ways to see which would most affect people's ultimate decision.

RESULTS: What turned out to matter most was the way in which the decision was framed. When asked to choose between CPR and a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, 60 percent of the participants went for CPR. But when the doctor used the phrase "allow natural death" instead, only 49 percent of patients chose resuscitation. In addition, when the doctor said, "In my experience, most people do not want CPR," only 48 percent decided to go against the norm and choose CPR anyway (versus 64 percent when they were told CPR was the more popular decision).

IMPLICATIONS: The experiment suggests that careful attention to word choice can help people rationalize tough decisions. The euphemisms doctors use matter, perhaps reducing guilt by suggesting that they're allowing something to happen, instead of interfering with a chance at survival. It helps, too, for people to believe they're making the socially acceptable choice. The participants probably didn't even realize they were being subtly manipulated: overall, 84 percent said they were confident that they had chosen for their loved ones what their loved ones would have chosen for themselves.

The full study "The Effect of Emotion and Physician Communication Behaviors on Surrogates' Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions: A Randomized Simulation Experiment," is published in the journal Critical Care Medicine.