Pitt campus finding cohesion of architectural style

When you think of the University of Pittsburgh, you can't help but envision the imposing 42-story Cathedral of Learning, with its inspiring Nationality Rooms, and, of course, the nearby Heinz Memorial Chapel — one of the finest college chapels anywhere.

But, in most other ways, this sprawling urban campus has always been distinguished architecturally mainly by a lack of distinction — with a large number of mundane buildings in a wide variety of styles, often set with no relationship to each other.

Yet, all of this is gradually changing today, as the university pursues a substantial program of modernization, additions and new buildings in a way that promises to gradually bring some coherence to a very diverse urban campus.

New dormitories built in recent years (a fine new one opened just last month), some stunning additions to existing science and engineering buildings, and even the giant Petersen Events Center all point the way toward a better future.

Moreover, there are now guidelines in place for the use of materials on buildings and an important signage program that makes all university buildings instantly identifiable.

It has taken quite a while, though, to establish any sense of cohesion.

Pitt settled in Oakland in the early 1900s, acquiring a 42-acre site along the steep side of Herron Hill, which rises some 250 feet above the Oakland plane.

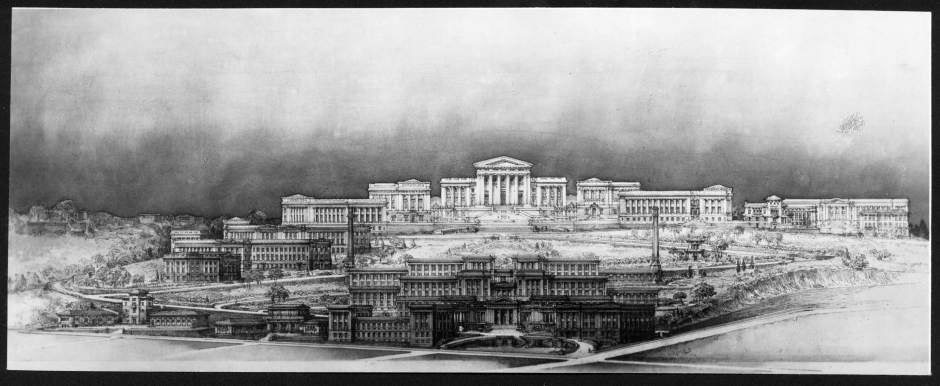

Architect Henry Hornbostel, a famous practitioner of the Beaux Arts who also designed Carnegie Mellon University's campus, prepared a 1908 master plan for a grand classical-style acropolis on this hill.

He envisioned 30 hillside structures that would look like Greek and Roman temples, culminating in a majestic “forum,” not far from where the Veterans Administration Hospital sits today. He thought underground escalators could be used to move students up and down the steep hill.

But only five of Hornbostel's buildings were built. Barely a dozen years later, an ambitious new chancellor, John Bowman, abruptly rejected the Acropolis idea. Bowman coveted the flat land at the center of Oakland for the university he dreamed of building. So, with the all-important support of brothers Andrew and Richard Beatty Mellon, he acquired land and set out to build his iconic skyscraper “Cathedral” — to symbolize the importance of the university to the city.

Bowman sought for this project one of the best-known collegiate architects of the day, Charles Klauder of Philadelphia. Klauder did major parts of much-admired campuses at Princeton, Duke and Yale. And he did not disappoint in Pittsburgh. Although modernist architects disdained his Gothicist style (Frank Lloyd Wright once called the Cathedral of Learning the “largest keep-off-the-grass sign” in the world) he did three finely wrought buildings for Bowman, including the Heinz Chapel and the Stephen Foster Memorial.

Yet, Pitt still had a disjointed campus. Even today, it has three distinct sections — the familiar flat areas around Forbes and Fifth avenues; the side of Herron Hill, where science, engineering and medical buildings predominate; and the top of the hill, where athletic facilities are clustered along with large newer dormitories and fraternities.

Pitt had a major opportunity to expand its lower campus after the late 1960s, when it became clear that Forbes Field would soon be torn down. But it did it incoherently, with buildings that are so different, it is the architectural equivalent of trying to play baseball, football and hockey — all on the same field and all at the same time.

Three of the buildings — Posvar and Lawrence halls and the Law School were rendered in the then-fashionable “brutalist” style, but without the sophistication that it takes to make brutalism attractive. They exhibit pretty much the worst modernist ideas of the time — overbearing, cold-feeling buildings with barren plazas between them.

A fourth, the Hillman Library, has a somewhat restrained but still quasi-brutalist facade. Yet, its podium wall is intended to echo the Renaissance-style rusticated stone base of the Carnegie Library across Schenley Plaza. Inside, contradictions continue. The main floor is serene — modeled on a different modern style, that of Mies van der Rohe, with lots of warm teak, black-metal framing and plenty of light.

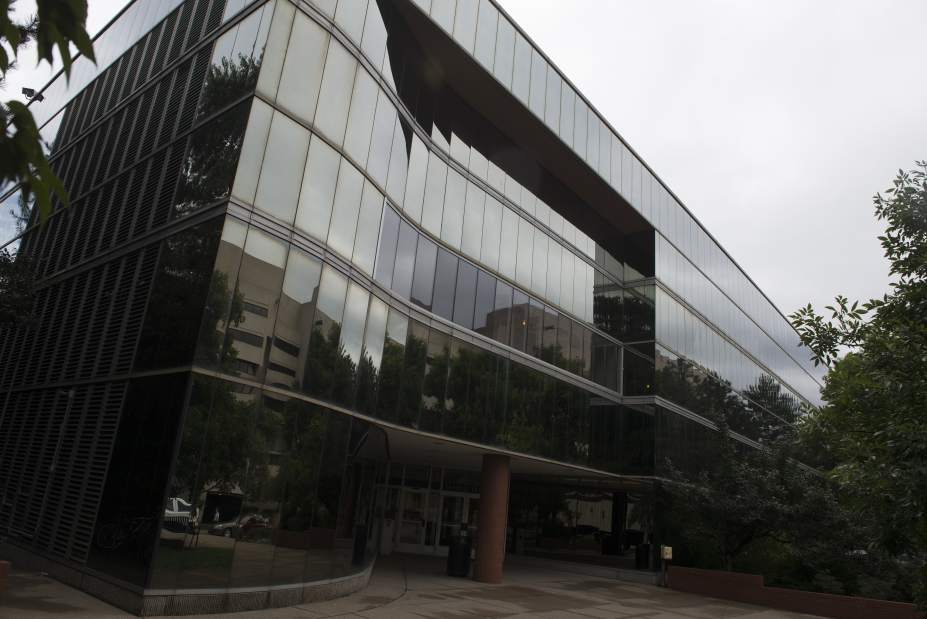

The later glass-walled Katz Graduate School of Business, also on the Forbes Field site, has a pleasing, dark, modern elegance and turned out much better. It's close by the Frick Fine Arts Building, a stone-and-marble imitation of an Italian Renaissance villa. The Frick building had nothing new in the way of architectural ideas about it, but both buildings have quality.

More recently, one of the worst of the barren spaces — between Posvar and Hillman — was rescued with an effective landscaping program that leads into the new Schenley Plaza. Hillman, in turn, was enhanced with restoration of its own plaza and entrance.

Other bright spots include the Mascaro Center, a recent addition to the engineering complex that provides some sophisticated excitement along O'Hara Street, and a deft addition to the Chevron Science Center that helps make a dull building look interesting. The 11-year-old Sennott Square building on Forbes and the just-opened Nordenberg Hall freshman dorm on Fifth are both done in the now-routine Post-Modern style. Though not visually challenging, they seek to harmonize with older non-university structures around them.

John Conti is a former news reporter who has written extensively over the years about architecture, planning and historic-preservation issues.